He had to wait until he was almost 40 before he had enough money to buy a horse, and ended up with broodmares others didn’t want. Then he was refused to breed these mares to the stallions of his choice and had to settle for an untested and relatively cheap debut stallion. Despite all this, Charlie W Williams bred an undefeated superstar of his time in Axtell, who in turn sired one of the sport’s foundation sires.

Williams was not born into money and had to work his way up. According to Ken McCarr in his book The Kentucky Harness Horse, “CW Williams, born in Chatham, New York, in 1856, was taken as a boy to Buchanan County, Iowa, where when not busy on his father’s farm he hired out to neighbors for twenty-five cents a day. Later the family moved to the town of Jesup, where young Williams was employed as a store clerk for five dollars a month plus board and the privilege of sleeping under the counter. After losing that job in the panic of 1873, Williams went to Chicago, where he drove a milk wagon and managed to save some of his twenty-dollar-a-month wages. Then he returned home, to high school and a night job at the railroad station, where he picked up telegraphy. After graduation, Williams started a business of his own, shipping Iowa butter and eggs to New York. He also became the night telegraph operator at Independence, Iowa, a few miles from Jesup, married and settled at Independence.”

Williams had a buckskin trotter which he raced at the county fairs, but the horse lacked ability and didn’t perform so well. The desire for a really good horse was strong in Williams, though, who spent quite a bit of time studying pedigrees. When Henry and Frank Stout at the Highland Stock Farm in Independence wanted to get rid of some its broodmares, they singled out several mares that failed to meet their standards. These included the unstarted duo of Gussie Wilkes and Lou, the latter with a pedigree void of Hambletonian and initially not even considered a standardbred. In 1884 Williams picked up the two mares for $125 and $75, respectively, and the following spring he sent them to Kentucky to be bred.

When it came to choosing stallions there was a “Wilkes craze” in the 1880s in Kentucky. George Wilkes had died in 1882, but numerous sons stood stud in the Bluegrass state, and Williams wanted his mares bred to sons of the diseased legend. Williams had entrusted the stallion selected to his employee John Hussey, who selected Red Wilkes and Baron Wilkes, both sons of George Wilkes, for each of the two mares. However, these two stallions were popular and the stallioneers were not interested in breeding their popular stallions to two cheap and unstarted mares from Iowa. Thus, Hussey was forced to settle for much less popular stallions. In the end, Gussie Wilkes was sent to Jay Bird, a roan horse who was going blind while Lou was bred to William L, a handsome, well-bred three-year-old with crooked hind legs. Both of these stallions were also son of George Wilkes.

The early years

On March 26, 1886, Lou gave birth to a brown colt, and five days later Gussie Wilkes did the same. In the beginning of July, John Hussey brought the mares, in foal to the same stallions, back to Iowa together with their foals. Given the background, one could easily expect little out of the colt pair, named Axtell and Allerton, to be highly average or worse – but instead they would turn out to be amazing trotters for a for a few years even made Independence, Iowa one of the trotting hotspots in the US. As an side, according to a report in The Terre Haute Express on Oct. 12, 1889, Axtell was named for “School Superintendent Axtell of the Independence, IA. public schools.” The future star didn’t make a great first impression, though. According to an article on Oct 31, 1889 in Rutland Weekly Herald, “When Axtell was foaled he was so small and had such bad, crooked and curly hocks that Mr Hussey, who had charge of Mr Williams’ stock, though the colt ought to be killed.”

According to the book Axtell and Allerton, by HC Harding, the duo was broken in late summer as yearlings. Harding points out that Axtell didn’t look like a star at first, and the following winter Williams even offered to sell the son of William L: “(…) it will not be amiss to state that Mr Williams did offer to sell him for three hundred dollars to a gentleman who was shipping a load of mares to Nebraska. This gentleman thought the price too high and offered two hundred and seventy-five dollars for him, which offer, as is well known, was refused. It was but a short time after, however, that it would have required thousands to buy him.”

In the summer of 1888, when Allerton and Axtell were two, Williams and Hussey realized both of the two-year-olds were super-talented. That fall, Williams sold his butter and egg business to devoted himself fully to his horses. At 2, Axtell was undefeated and lowered the two-year-old stallion record to 2:23 (1.28,9) which he trotted in Lexington. When Axtell trotted trotted that time, it was described as “late in the afternoon on a raw, unfavorable day and over a track by no means in condition for speed.” Several reports pointed out that with favorable conditions Axtell could be expected to trot in 2:20 (1.27) at 2.

The record season

At the beginning of 1889-season, the three-year-old record stood at 2:18 (1.25,8). Axtell and the Califonia filly Sunol, however, would take turns lowering the record in the fall, not stopping until they had slashed seven and a half seconds off. After trotting a new record for the age group in 2:14 3/4 (1.23,7) at Cleveland, Axtell lowered that to 2:14 (1.23,3) at the racing meeting of the Northwestern Breeders’ Association at Washington Park, Chicago in early September. That started a frenzied few months of new records. In the beginning of October, Sunol shaved a quarter off the record 2:13 3/4 (1.23,1). On Oct 11, 1889, Axtell put in his greatest performance in a time trial in Terra Haute. There Williams and Axtell reached the first quarter in :33 and the half in 1:05 1/2. According to an article in the Chicago Tribune the following day, that caused Colonel John W Conley to exclaim “too fast”, a sentiment shared by many as a sigh went up from the crowd. The colt, however, was still game. A third quarter of 32 1/2 made people believe again, and “without a wabble or false step he finished the mile strong in 2:12 (1.22,0).

In a local newspaper, Williams stated that “Axtell wore only protecting boots, five-ounce shoes in front and three-ounce behind, with no weights. I never sat behind him when he was so full of trot. I am sure that if I had a month more chance to work with him sharply, with periods of rest, he could go a mile in 2:10.”

That very same night, the above-mentioned Colonel Conley head a syndicate which bought the three-year-old for a record $105,000. “It is like selling a child”, said Williams after reluctantly accepting the offer. It was the highest price ever paid for a horse of any kind at that time. Axtell’s world record wouldn’t survive long, though. One month later Leland Stanford’s filly Sunol trotted in 2:10 1/2 (1.21,1) at San Francisco, becoming the fastest three-year-old up to that point.

An average sire

In Sun-Journal at the end of 1889 it was reported that “R.S. Veech, Indian Hill Farm, St Mathews, KY, has booked seventeen of his choice matrons to Axtell for 1890 at $1,000 each. It may be recalled by some of our readers that the proprietor of Stony Ford, one year, bred thirty-two mares to Rysdyk’s Hambletonian at $500 each, but he reaped large returns on the investment.” The same month is was also announced that Axtell already had a full book of 90 mares for the upcoming breeding season – despite being priced at a hefty $1,000 stud fee. Anxious to get a return on their massive investment, the syndicate kept the stud fee at a stiff $1,000 – double that of St Simon, the most popular thoroughbred stallion at the time – for three years. After that, the panic of 1893 hit, but with high interest from breeders Axtell had already paid for himself. That was just as well, because interest in Axtell was soon to wane because of his get’s inability to deliver on the tracks. Axtell made his owners money, but little for the breeders who used his services.

Though he had some good sons and daughters, Axtell was nowhere near the star stallion category: none of his get was ever among the three best in the Kentucky Futurity, the biggest race of three-year-olds in his lifetime. His best trotters were Ozanam 2:07 (1.18,9), Elloree 2:08 1/4 (1.19,7), Ernest Axtell 2:08 1/4 (1.19,7), Angle 2:08 1/2 (1.19,9), Praytell 4, 2:09 1/2 (1.20,5) and Mainland 2:09 1/2 (1.20,5). Of these, Elloree is 3×3, while Ernest Axtell and Angle are 3×4, on George Wilkes. While Axworthy, mentioned below, was by far Axtell’s best son at stud, Ernest Axtell, from his sire’s last crop in 1907, was exported to Austria and became a very good stallion. There he sired Heinrich, born 1927, one of Austria’s best trotters ever.

In his second season at stud Axtell was bred to Marguerite and produced Axworthy, a chestnut who had problems with lameness yet became one of the five foundation sires in US harness racing. But lameness is a key issue in this story. Bad hind legs, a characteristic of both Lou and William L, prevented Axtell from returning to the track at four, and this defect was something he passed on to much of his get. Axtell, who stood stud at WP Ijams’ farm at Terre Haute, Indiana, didn’t even impress people at the farm itself. According to McCarr, Ijams once uttered “I think more of my Jersey bull than I do of Axtell.” In fairness, Axtell wasn’t terrible at stud and had some good sons and daughters, but none had the raw ability he himself had displayed. Axworthy’s most important son at stud, Guy Axworthy, was an almost true copy of Axtell and also had issues with his feet.

After selling Axtell, Williams got busy on his own. With the massive amount of money from selling the colt he built a farm, a streetcar line and a kite-shaped track, named Rush Park, at his home in Independence, Iowa. Kite-shaped tracks were considered the fastest type of racetrack and numerous horses were shipped to the otherwise completely unknown Iowa town. The panic of 1893, where unemployment rose to over 40 percent in parts of the country, wiped all that out.

Due to Axtell’s failure to reproduce his great speed at stud he lost popularity as a sire and was eventually put up for auction in November 1900. At the Old Glory auction he was sold for for $14,700 to Fred Moran and WP Ijams, both members of the syndicate that owned him up to that point. Axtell died on August 19, 1906 in Terre Haute, Indiana.

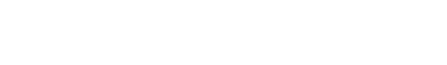

Axtell

Bay colt born in Iowa on Mar 26, 1886. Died in Terre Haute, IN on Aug 19, 1906.

William L – Lou (Mambrino Boy)

3, T2:12 (1.22,0)

Breeder: Charlie W Williams

Owners: Charlie W Williams – Axtell Syndicate – Fred Moran, WP Ijams

Trainer: Charlie W Williams

Driver: Charlie W Williams

Groom: –